FDA Clears OsteoFab: 3D Printing Brings Facial Reconstruction Into The Future With Perfectly Precise Molds

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a first-of-its-kind facial reconstruction implant from Oxford Performance Materials, Inc., a manufacturing company now emerging as a pioneer in 3D-printed jaws and faces.

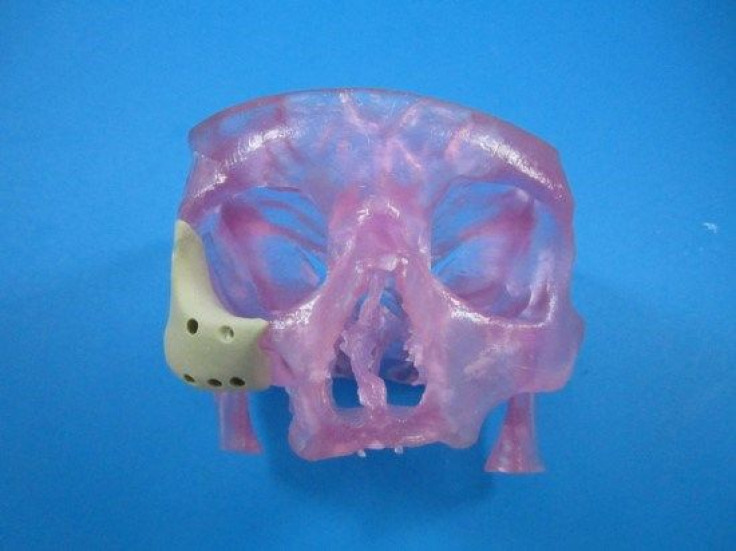

The new polymer device follows the February 2013 approval of the Osteofab Patient-Specific Cranial Device. It builds upon prior research into 3D-printed reconstruction, specifically with regards to cheek and jaw bones — complex parts of human anatomy that, so far, have demanded invasive methods that borrow skin and bone from other areas on the body.

"There has been a substantial unmet need in personalized medicine for truly individualized — yet economical — solutions for facial reconstruction,” said Scott DeFelice, CEO of Oxford Performance Materials, in a statement. “And the FDA's clearance of OPM's latest orthopedic implant marks a new era in the standard of care for facial reconstruction.”

In prior decades, facial reconstruction involved the dangerous and delicate removal of a patient’s skin and bone, typically from the hip and thigh, to fashion the missing pieces of skull and mandible. These procedures, known as autografts, are invasive and don’t leave much room for specificity. Shaping a hip bone into a jawbone requires a great deal of effort and skill, which a patient may expect a doctor to have in spades; however, the risks of infection and improper healing always remain.

More recently, scientists have developed a putty of sorts, which they can use to mold new bones and trust they’ll keep their shape, particularly as the material hardens and the biodegradable scaffolds dissolve. They call it a shape-memory polymer (SMP), and it facilitates the growth of new bone cells, called osteoblasts.

The latest device uses a similar principle in the later stages, but with a refined beginning. Rather than rely on a pair of hands to manually form the patient’s new face, doctors can use an MRI or CT scan to digitize the skin’s topography. That file can then be sent to a 3D printer to manufacture a new polymer face, which surgeons would implant into the patient.

In addition to the process’ scientific novelty, practical matters of cost also make the device attractive for patients. “This is a classic example of a paradigm shift in which technology advances to meet both the patient's needs and the cost realities of the overall healthcare system,” DeFelice said. Autografting and the resultant hospital stay far exceed the precision and quickness of the new implant. Patients will spend less time in the OR and pay less out-of-pocket.

The FDA’s approval also means orthopedics as a whole is set to benefit, given the previous successes with cranial implant devices. “These are disruptive changes that will allow the industry to provide the finest levels of healthcare to more people at a lower cost,” said Severine Zygmont, President of OPM Biomedical.

The device is likely just the next in a long line of 3D-printed biomedical advances, coming on the heels of 3D-printed prosthetic limbs, blood vessels, windpipes, and “bioficial” hearts. Synthetic replacements for the body’s normal bank of organs have existed for decades, and 3D printing is slated to optimize the existing process even further, and not just in the classic animal models of a lab but on real-live humans.

"Until now, a technology did not exist that could treat the highly complex anatomy of these demanding cases,” DeFelice said. “With the clearance of our 3D-printed facial device, we now have the ability to treat these extremely complex cases in a highly effective and economical way.”