McGill-born technology aims to revolutionize headphones, speakers

Ora's technology uses graphene, a 'wonder material' that has yet to fulfill its promise

Article content

Serendipity is the brother of invention.

A Montreal startup is counting on technology sparked by a casual conversation between two brothers pursuing PhDs at McGill University.

They were chatting about their disparate research areas — one, in engineering, was working on using graphene, a form of carbon, in batteries; the other, in music, was looking at the impact of electronics on the perception of audio quality.

At first glance, the invention that ensued sounds humdrum.

It’s a replacement for an item you use every day. It’s paper thin, you probably don’t realize it’s there and its design has not changed much in more than a century. Called a membrane or diaphragm, it’s the part of a loudspeaker that vibrates to create the sound from the headphones over your ears, the wireless speaker on your desk, the cellphone in your hand.

Ora — the company that eventually emerged from the conversation between Robert-Eric Gaskell and Peter Gaskell — says it has developed a lighter and more rigid membrane that can improve sound and extend battery life of portable speakers and cellphones.

Membranes are normally made of paper, Mylar or aluminum.

Ora’s innovation uses graphene, a remarkable material whose discovery garnered two scientists the 2010 Nobel Prize in physics but which has yet to fulfill its promise.

“Because it’s so stiff, our membrane gets better sound quality,” said Robert-Eric Gaskell, who obtained his PhD in sound recording in 2015. “It can produce more sound with less distortion, and the sound that you hear is more true to the original sound intended by the artist.

“And because it’s so light, we get better efficiency — the lighter it is, the less energy it takes.”

In the early days, Ora had it sights set on the headphone market, where growth potential was great — 2014 was the year Apple purchased headphone maker Beats Electronics for US$3 billion. But Ora has since broadened its ambition, in an effort to tap into other multibillion-dollar markets.

Many people listen to music from phones and tablets without earphones or headphones, explained Thomas Szkopek, who was Peter Gaskell’s PhD supervisor and now sits on Ora’s advisory board.

“The visual experience of electronic devices is very appealing but the sound reproduction leaves a lot to be desired,” noted Szkopek, an associate professor at McGill’s electrical and computer engineering department.

In January, the company demonstrated its membrane in headphones at the Consumer Electronics Show, a big trade convention in Las Vegas.

Six cellphone manufacturers expressed interest in Ora’s technology, some of which are now trying prototypes, said Ari Pinkas, in charge of product marketing at Ora. “We’re talking about big cellphone manufacturers — big, recognizable names,” he said.

Technology companies are intrigued by the idea of using Ora’s technology to make smaller speakers so they can squeeze other things, such as bigger batteries, into the limited space in electronic devices, Pinkas said. Others might want to use Ora’s membrane to allow their devices to play music louder, he added.

Makers of regular speakers, hearing aids and virtual-reality headsets have also expressed interest, Pinkas said.

Ora is still working on headphones.

Consumers can pre-order a pair of Ora-brand headphones on the company’s website (it plans to soon move the effort to a crowdfunding site). The expected cost of the headphones: $500 to $600 per pair. Ora claims the sound quality will be as good as headphones that cost three or more times that much.

“Having our own line of headphones is a fast way of showing there’s a market for our product, and to show potential investors the value of the company,” Robert-Eric Gaskell said.

***

Ora’s material of choice — graphene — is a form of carbon. “As a material it is completely new — not only the thinnest ever but also the strongest,” the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted when it awarded the Nobel Prize to physicists Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, who first isolated the material.

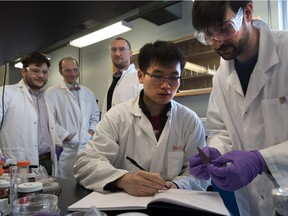

Ora’s process starts with graphene dispersed in water, Szkopek explained during a tour of a laboratory the company uses at McGill. Then, the solution is dried out.

“Part of the company secret is what we do to the graphene that’s sitting in the water — the things we do to it and how we get it to take these different shapes is part of the magic we’ve developed in the lab,” Szkopek said.

“What’s most exciting about this work is that no one has yet found the application that is going to bring graphene material into people’s daily lives,” he added. “Here we have a sweet spot — there’s an intersection between a need in the consumer market and some of the fantastic properties that graphene has.”

Graphene is now used in some products — to strengthen some sports equipment such as tennis rackets, for example. But efforts to commercialize it on a large scale have taken longer than expected.

“Graphene has been called a ‘wonder material’, as it offers an unrivalled combination of tensile, electrical, thermal and optical properties,” the consulting firm Deloitte noted last year. “Yet, it may be decades before this material’s potential is fully realized,” in part because “despite many academic and commercial research groups investigating methods of production, making large quantities of graphene remains a profound challenge.”

Ora, for its part, thinks it “may be one of the first companies to actually have a commercially viable product that uses mostly graphene,” Pinkas said.

***

With McGill’s help, the inventors filed for a patent in 2014 and later that year presented a paper about the concept at an Audio Engineering Society convention.

“It was completely unfunded at the beginning,” Szkopek said. “It was curiosity-based research.”

The idea got a boost in 2015 when it garnered an alumni-funded $7,000 innovation award from McGill’s engineering faculty. The money was used to hire a summer student to come up with a prototype.

That in turn helped the company attract $500,000 in seed money last year from TandemLaunch, an incubator that finances early-stage technology developed in universities. That allowed Ora to hire staff — it has five employees — and to develop and start marketing the product.

Ora’s technology has received attention in high-fidelity, engineering and science publications, but it will have to get its products into consumers’ hands to prove it has real potential.

First though, the company hopes to hire a seasoned chief executive in the next few months whose primary role will be to raise a first round of venture capital.

At the moment, it’s looking into ramping up production.

Ora’s raw-material costs are slightly higher than those of Mylar polyester film (used in many types of speakers) but on par with aluminum (often used in cellphone speakers), Robert-Eric Gaskell said.

If it can keep manufacturing costs reasonable, Ora will be within the range electronics manufacturers would consider paying for membranes, he added.

“Our biggest challenge is making the leap from the lab to the factory,” Gaskell said.”We have yet to take it from making five or 10 at a time in a lab to making 500,000 at a time in a factory.”

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.